“Bone Strikes” Using an Open Hand

January 31, 2017

“A lot of people don’t appreciate that palms can be even more devastating than a fist in a lot of circumstances…the dummy really makes you aware of that because most of the striking on the wooden dummy is done with open hands, so its telling you something also quite crucial – that your hand is a very effective weapon.”

Sifu David Peterson

The Chinese have many sayings – one of the more general martial art sayings is “fist to the body – open hand to the head.”

Although the chained punch is the principal weapon of the Wing Chun system, it requires some prerequisites, particularly conditioning the hand. Since conditioning the hand takes many years of steady training (and must be maintained), most people aren’t doing it!

How many of us are really conditioning our hands to the necessary degree?

To properly condition your hands, you should be hitting the wallbag every day in a progressive manner, then maintaining that conditioning once achieved. It takes a long time (a year or two) to really get Wolf’s Law working on your behalf — to actually modify the structure of your hand and develop the bones and tendons. And you also have to have impeccable technique, relaxing at the right time and tightening at the right time. It takes a lot of training to do it right.

This is a big, big overlooked problem in Wing Chun training.

Students are punching the wallbag for a few minutes and maybe doing some pad drills and then spending many hours developing a reflex to punch people in the head. Someone said, “don’t put in part-time efforts and expect Championship results.” The “conditioning the hand” to “training to hit the head” ratio is not that great!

If you don’t condition your hands, hitting someone in the head as hard as you can is a recipe for disaster!

If strike someone in the skull with your fist, 95% of the angles and targets will provide a good opportunity for a broken hand, and in many cases, a shattered hand. The harder you punch, the more you will damage not only your opponent but yourself. Physics tell us forces will generate an “equal and opposite” reaction.

While this Luke Cage image (where a bad guy shatters his hand on Luke’s bulletproof head) may be an extreme example, its certainly possible, especially if your fist lands on a really thick section of the skull (like if the opponent ducks and you hit them in the top of the head).

While this Luke Cage image (where a bad guy shatters his hand on Luke’s bulletproof head) may be an extreme example, its certainly possible, especially if your fist lands on a really thick section of the skull (like if the opponent ducks and you hit them in the top of the head).

This is why the Palm Strike was invented (or as UFC ex-Champ Bas Rutten calls it, a “bone strike”).

If this is true, why do we rely on the punch at all?

The problem with the Palm strike is it requires that you get a little closer to your target (a few inches closer). Closer is considered less safe for Wing Chun and boxing (this is why reach is shown in the pre-fight “tale of the tape”).

Inches are like miles at this range. This is also the problem with elbow strikes, and why Wing Chun typically only uses the elbow to break a grab. We don’t usually use elbows to strike the head because going in that close really speeds things up.

The closer you are (or if you are “inside”), the faster things happen, and the less time you have to react. Our bent arm hitting range was selected for its specific characteristics. Its close enough but not too close. Its the Goldilocks distance for hitting — just right. You have to get this close to hit with structure, but its dangerous so we also try to protect ourselves by keeping our hands up and in the playing field, attempting to maintain two hands on top, trying to move to the outside if possible, and chaining the attack to make it a barrage that is more difficult to defend (among other tactics).

Why do we ignore the Palm in our training?

In one sense, we don’t ignore it.

One of the classic indicators of how important a technique is in a Chinese martial system is how often (and how early) it occurs in the drills. In Wing Chun, the most important drill is the first one, the Siu Lum Tao. Although Chum Kiu tells us how to move, SLT tells us how to use our most basic strikes. And if we go by SLT, we should the Palm quite a bit — I count seven open-hand actions in the Siu Lum Tao (including Gaan, etc).

Plus, as Sifu Peterson notes in the opening quote, almost all the strikes in the Wing Chun Wooden Dummy are palm strikes, and this is for the same reason we have to be concerned about hitting the head. It doesn’t feel too good to punch a tree.

My favorite strike with the open hand has the fingers pointing to the two o’clock (on the right) or eleven o’clock (on the left) position. If you perform it correctly, arching the hand away from the wrist, it will hit the target with what they call the “distal” ends of the radius and ulna (the two bones that make up your forearm). You basically stab the opponent in the head with the blunt, thick knobs that are the ends those two bones. Plus the bones themselves are strong and flexible and very, very unlikely to break.

One the problems about demo-ing Wing Chun actions is that we don’t want to beat up on our students to provide a clear example of what a particular action will do in practice. So we have to use our imaginations. I am starting to play around with video to try and get closer to a demos that capture what would happen in a real Wing Chun street fight. Below, I cut together various bits of my training to help show (by implication) what would happen if I was able to get one or more of these “bone strikes” through and hit my opponent in the head with them.

I find its not to difficult in real life (with a moving, dodging opponent) to pull off a strike with the elbow down and the fingers pointing at two o’clock. The “fingers pointing to the twelve o’clock” palm strikes are easy to do on a pad and on “Bob” (the rubber man) but a little more difficult on a moving target. The “two o’clock” strike would probably be pretty devastating from a fence-type position, as a surprise opening shot, which I also show in this clip (hitting to the chest for safety).

NOTE: You’ll see Buka and I training something I got from Geoff Thompson. Your training partner holds the pad. You put one hand on the edge of the pad or one their shoulder. This is meant to simulate a “hey, I don’t want any trouble” friendly talking with the hands, which can also be deception and an un-threatening fence.

It helps me to think of this action less as a “hitting the head with the palm” and more like I’m “stabbing them in the head with the bone.” I actually use this imagery for punching as well. Think of your elbow as a hand holding a sword and everything forward of the elbow as the sword. If they get their hands up and you get on the outside, you can stab this “sword” through the “V notch” (gunsight) of the opponent’s raised bent arm. As above.

Rinse and repeat.

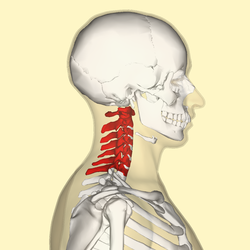

A great adjustment if you miss is illustrated at the very beginning of the Wooden Dummy. You throw your strike and the opponent dodges to one side. You reach past them and then turn that into a neck pull, yanking the opponent’s head down into the next incoming palm strike. You miss the punch, then pull the hand back (in a kind of jutt action), slapping the “jade pillow” (nape of the neck, location of cervical spine) with the inside of the hand. Pull the elbow down sharply.

A great adjustment if you miss is illustrated at the very beginning of the Wooden Dummy. You throw your strike and the opponent dodges to one side. You reach past them and then turn that into a neck pull, yanking the opponent’s head down into the next incoming palm strike. You miss the punch, then pull the hand back (in a kind of jutt action), slapping the “jade pillow” (nape of the neck, location of cervical spine) with the inside of the hand. Pull the elbow down sharply.

Be very careful with this in training! Only do it very slow and miming the action, as it is very easy to hurt your training partner, even with the lightest touch! But you can yank the dummy as hard as you like.

The idea is to train to pull the head forward into the elbow-driven bone ends of the radius and ulna. If you look at an x-ray, the bones of your forearm look like a pair of clubs (and probably were used for this back in pre-history).

Here is Bas Rutten saying more or less the same thing, although he is advocating a direct attack to the “jade pillow” (back of the neck) or a clothes-line style strike to the area behind the ear.