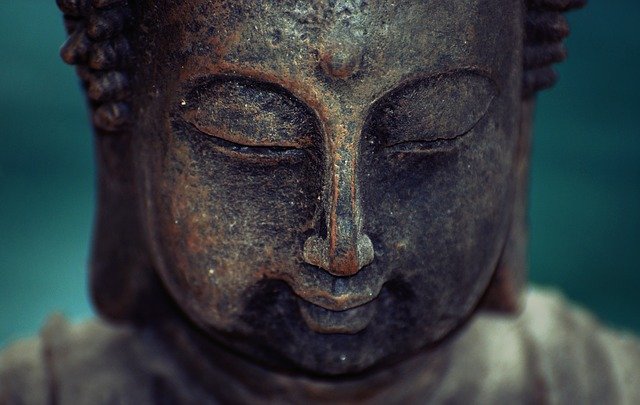

Buddha: Desire and Frustration

May 23, 2022

Here we have a statement of the Four Truths, which are not four principles, but merely one principle, with four statements asserted about it. The principle: desire for what will not be attained ends in frustration; therefore, to avoid frustration, avoid desiring what will not be attained. The four statements: (1) Unhappiness consists in frustration (dissatisfaction, anxiety). (2) It originates in desiring what will not be attained. (3) It ceases when one ceases to desire what will not be attained. (4) The method is to seek the middle way between wanting things to be more than they are or less than they are with respect to the way that they are. If this be Gotama’s doctrine, surely we are all followers of Gotoma, assenting to the truth of his principle, even if, unhappily, we fail to practice it to perfection.”

The Philosophy of the Buddha

So – basically – want what you have. Don’t desire what you cannot have. If you are injured, accept it. If you might die, accept it.

Awareness in fighting is about acceptance. Accepting what is allows us to not “gild the lily” but to be open to what is actually happening. If we are always resisting reality (“It’s not so bad!” or “This sucks!” or “I don’t believe it”) then we are in the habit of deceiving ourselves and this colors over into fighting. How do we enter a fight calmly and just respond to what happens (not what we imagine to be happening, colored by fear and anxiety).

In Buddhism, they talk of clinging to an outcome. This is clinging. How do we not concern ourselves with the outcome of the fight but stay in the moment and respond to what is happening now, without anxiety over what might happen (injury, death)?

In discussions of Zen in the context of sword fighting, they talk of being on the razor’s edge, or the edge of the sword. Death is on either side and the warrior has equanimity. To die is simply to return to the “all.” Can we find that place, on the edge of the sword, and stay there, all the time?

In Band of Brothers , the HBO show about World War II and the paratroopers who jumped behind enemy lines at D-Day, there is one Lieutenant who amazes all the troops with his bravery. He doesn’t seem to fear death. At one point, there is an enemy machine gun set up by a farmhouse controlling a field of fire they need to cross. Everyone is pinned down, under cover. The Lieutenant jogs across the field of fire like he’s jogging down a suburban street in peacetime and flanks the machine gun. Later, a soldier name Blythe confesses to the officer how afraid he is and how this is debilitating him.

“Blythe,” the Lieutenant says,”the only hope you have is to accept the fact that you’re already dead.”