Deadly Calm Discipline

December 10, 2015

(

t

ranscribed from newspaper clip from

The West Australian

1988)

(

t

ranscribed from newspaper clip from

The West Australian

1988)

Shafts of light jumped from the polished blades as they sliced through the air, each movement was fast, precise, and undoubtedly deadly in combat.

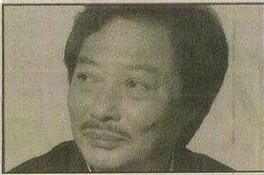

The face of Sifu Wong was calm and his pleasure was obvious as he became absorbed in a routine of skillful and beautifully rhythmical Wing Chun movements.

Earlier, sitting back on the lounge chatting, Wong Shun Leung had appeared placid—almost meek. But as he ran through some of the Wing Chun movements dressed in his traditional robe, he radiated strength and purpose.

Sifu Wong (sifu means instructor) is a Master of Wing Chun – one of the many martial art disciplines. As a young man he proved himself as a formidable fighter and excelled at his WIng Chun training.

He was a disciple of the late Wing Chun grand master Yip Man and was both friend and instructor to silver screen hero Bruce Lee.

But Wing Chun is not his life. At 53, the most important thing is that everything goes well. He lives with his wife, two sons and daughter in Hong Kong.

Sifu Wong enjoys dispelling the myths that shroud martial arts – about its inherent mysticism and the reasons for learning it.

“Martial artists are not people who learn magical powers to become mystical monks like the movies portray,” he said, obviously not for the first time.

“A lot of Kung Fu styles in the past have lived off reputations of having some magical secret level that you can obtain and, unfortunately, some instructors have carried on this silly idea.”

Sifu Wong is adamant that Wing Chun is not practiced simply for its fighting skills; it is a skill based on logic and economy of being.

“Wing Chun is a scientific skill that individuals practice to discover their limitations and find peace within themselves,” he said.

“We don’t train simply for the purpose of combat. There are a lot of things to which you can apply the Wing Chun thought process – of being simple and economical in the way you move and think.”

Undoubtedly, Hollywood is largely to blame for placing the martial arts on a blazing pedestal with its portrayal of invincible warriors guided by mystical forces – immune to pain and having unlimited strength.

Sifu Wong said that although Bruce Lee’s career in the movies helped build this image, it also drew a lot of attention to martial arts.

The history of Wing Chun is clouded by legends, but it can be clearly traced from the 1940s in Hong Kong where a Chinese man named Yip Man was primarily responsible for its development and present popularity.

Yip Man came from a very wealthy family. When the communists began their rise in China he feared he would lose everything so moved to Hong Kong. He did not begin teaching Wing Chun until he was more than 50 years old and needed a job.

Sifu Wong became a student of Yip Man when he was 17. He had practiced other forms of martial arts – mostly on the streets – but turned to Wing Chun when he failed to beat the old man in a sparring match.

Sifu Wong said he had achieved a balance in his life through Wing Chun training. This would account for his calm and gentle manner – a contrast to his fighting techniques.

He said the best way to get out of a situation was without a fight, but you didn’t always know if this was possible and therefore the fighting skills were important.

Despite his fiery nature as a youth he has never fought simply for its own sake.

“After I learnt the skills of Wing Chun from Yip Man I often had the opportunity to test them,” he said. “By experimenting with my skills I could discover their limitations and how they compared with other disciplines and so improve myself.

“After a time of this experimenting I learnt that I needed to rely less on the fighting part to get that self-satisfaction and feeling of achievement.”

A feature of Wing Chun is that it does not have set ideas and techniques. “It is a lot more open to your use – it doesn’t use you,” he said.

Sifu Wong said that if the rivalries that existed between the various martial arts was a way of experimenting and testing skills, then that was good thing.

But the popular disciplines had become so well developed that fighting to learn was no longer very important.