How to Win a Fight

January 05, 2017

“I fight a centerline – I don’t fight a person…if you stop that (punch), if you block…I reorganize the punch back to the centerline.”

Greg LeBlanc

Its New Years and time for a little reflection.

This year marks my 17th year studying Wing Chun (minus 3 years ) and my 9th year anniversary studying with Greg LeBlanc (minus a year out on injury) will be in April.

What have I learned about fighting?

The single most important thing I’ve learned is that the principles we follow to win are almost too simple to comprehend .

Humans really like to over-complicate things!

I think this is what Bruce Lee meant in his famous quote:

“Before I learned the art, a punch was just a punch, and a kick, just a kick.

After I learned the art, a punch was no longer a punch, a kick, no longer a kick.

Now that I understand the art, a punch is just a punch and a kick is just a kick.”

We start wanting to learn “how to fight.”

Then we start taking classes. We start to get a general idea about all the elements involved in the curriculum (in Wing Chun, this means six forms and dozens of drills and exercises for various areas) and the confusion kicks in and it starts to seem a little oppressive. And Wing Chun is usually considered a pretty compact system! So at first its a lot and we are a little over-whelmed and not exactly sure what it all means relative to the sort of fights we’ve seen (in real life or in the movies). We’ve never seen anyone do anything like these movements in a real fight!

I remember having conversations with fellow students back in the beginning as we tried to puzzle out exactly how Wing Chun would look in a fight against a normal somewhat skilled opponent, thesort of fights you can see on Youtube (and in high school). Flurries of fast hooks, haymakers, overhand rights and lefts, and grabby attempts to grapple.

What would the Wing Chun guy do, we wondered? Chain punch? How would that look exactly?

In Wing Chun, the early training leads to an fixation on the hands. New students are always looking down at their hands, since its difficult to make them do these strange movements without watching yourself and trying to consciously control what the arms are doing.

The teacher seem so smooth! They can do series of the more “sophisticated” movements (like Kwan Sao or Po Pai ) with hits in there, all in a blended and relaxed series of fluid actions. When you watch Gary Lam do it, it seems so easy! But when a new student tries it, they perform an awkward mishmash of actions , plus they get hit.

When you come out of the other side of the training after a few years and have been exposed to everything, it starts to settle down.

The forms suddenly seem very short. You can do each form in a few minutes! They take so long to learn, but eventually they seem over very quickly. You start to realize there are not very many “hands” and the system really starts to seem pretty small.

Most importantly, you begin to understand that in a real fight, you will only use a tiny fraction of the system, usually the most basic movements. You will mainly attack with punches. The punch is the heart of the system. There are many technical details which add up to the ability to punch hard and rapidly punch again, but these punches are just punches.

So the main thing I’ve learned is I just want to hit them in the head .

You ever see the great action film “Executive Action?” In it, the hero is taking lessons on flying a small plane. His teacher tells him, remember, just fly the plane . This is to help him get out of his head and quit thinking nervously about flaps and landing gear and altitude as these confusing pile of separate things. They are all one thing — flying the plane.

All the stuff we learn (stance, stepping, facing, centerline, sinking, fook say, tan da) are just elements designed to enable you to hit that opponent in the head as hard as possible, as many times as possible, as quickly as possible.

What does Greg mean by “centerline?”

The whole system is designed to allow you to punch along an unobstructed line into your opponent’s centerline, which is the center of their “mass” or body. Usually we want to strike into the head. The centerline is a conceptual idea which allows us to “chase center” with our punches. Rather than hit the surface, we strike at the center of the body, no matter where we are relative to the opponent.

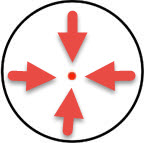

Think of a view from above the person.

The circle is their head. The centerline is that dot in the middle. Hit that.

The circle is their head. The centerline is that dot in the middle. Hit that.

All flight paths of your fist want to travel to that center.

If the circle is an approximation of their body, hit into the core of that (a little in from the spine, basically). This is where their weight is balancing on top of their pelvis.

Strike into their body or head with the intent not just hit the surface, but to penetrate .

Of course, you can’t actually punch a hole into their body (unless you are playing Street Fighter ). So what happens is you displace their body. Where their head or organ was a second ago, now your fist is there, briefly. Their head or body moves away at the same rate that your fist moves forward (while inside their body, actions we would need to describe medically or using terms from physics, like fluid dynamics, are happening, with possibly catastrophic results). The brain is thrown around. The organs are displaced. Perhaps bones are fractured. Then the second punch arrives. And the third.

All on the same point, like the beak of a woodpecker. Hammering on that successively weakened point.

“You know the meaning of Wing Chun? The meaning of Wing Chun is learn to take over your opponent’s position. Chinese, we say “seg wai.” Seg Wai is “I eat your position.” That means I take over your position. If I take over your position, I become you. You are controlled by me because you are out of balance already.”

Gary Lam

Any Cantonese speakers/readers out there — I would love to know if my spelling is correct and what the exact English definition is of this phrase “Seg Wai.”

This is the HOW of Wing Chun.

All our technology (stance, stepping, Dan Tien, conditioning of the hands, elbow down, structure) supports this displacing of the opponent, this sharp pointed attack which jars their skull (and the brain inside) or unbalances them (or both). Jarring the skull can cause unconsciousness. Unbalancing takes away their ability to retaliate with structure. They may fall back or down. It is hard to continue an attack when you are falling down.

If we remember this goal, then we can answer many of our own questions about the why behind the what in Wing Chun.

Why do we use certain hands? Pak clears the hands that are in the way of our path to the head. Lap clears the hands that are in the way of our path to the head (and may unbalance). Toi turns the opponent, taking away their facing, clearing the path to the head. Most of our Chin Na locks and arms bars are meant to drive the head into a wall or the ground. We are still hitting the head.

Why do we use certain hands? Pak clears the hands that are in the way of our path to the head. Lap clears the hands that are in the way of our path to the head (and may unbalance). Toi turns the opponent, taking away their facing, clearing the path to the head. Most of our Chin Na locks and arms bars are meant to drive the head into a wall or the ground. We are still hitting the head.

This all of course, sounds grim and violent, because it is! Wing Chun should be in a glass case that says “break in case of a threat upon your life!”

Once you break that (metaphorical) glass, your goal is clear.

Watch Greg in that training video – watch his punches and how his body lines up behind the punch and how his other hand clears or helps to expose the centerline of his partner to attack. The attacks all go in on a straight relentless line. You could draw those lines with a ruler, from Greg’s center to the opponent’s center.

Remember how I said I had conversations with fellow students back in the beginning as we tried to puzzle out exactly how Wing Chun would look in a fight? We wondered what the Wing Chun guy do and how it would look.

The Ip Man fight against the Japanese Black Belts is not a bad reference. Just subtract 9 guys and reduce the actions to a very few. The firsts would not be dribbling on the opponent’s head like a basketball. If you learn to support your punches, ideally it should not take 30 hits.

My student, he says, “Sifu, I hit the guy ten times, then he run away.” I say, “How can you hit him ten times and he can run away? You should tell me you hit him two times and he already sleep on the floor. OK, go and hit the sandbag five hundred times.”

Gary Lam