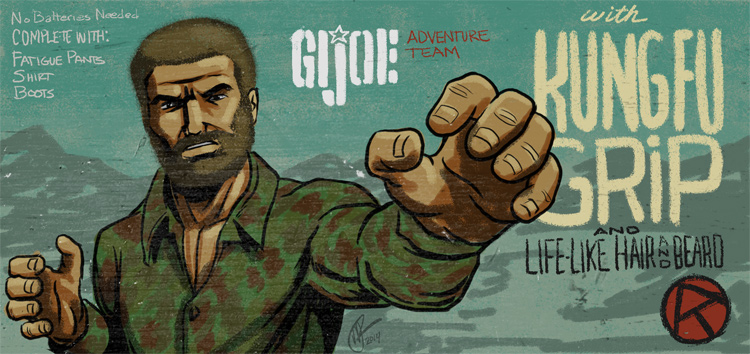

Now with Kung Fu Grip!

November 15, 2016

“The classic trope of the hero’s journey demands that the hero figure venture far away from home and face exotic danger to fulfill his/her destiny.”

Jared Miracle

We’ve had a burst of academic activity in the area of martial arts study this year (or maybe I just wasn’t paying attention before).

Since I started reading the website Kung Fu Tea , overseen and often written by academic writer and Wing Chun practitioner Ben Judkins (currently a Visiting Scholar at Cornell University and author of Creation of Wing Chun, The: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts with Jon Nielson), I’ve been more on top of the books in this area.

I am a recovering academic myself (having done a MA in English Literature and a Library degree and now working at UC Berkeley), so following doctor’s orders, I have mostly avoided reading academic articles and books since my last schoolwork in 2008.

Some of these works do suffer from the issues plaguing much academic writing, namely they are sometimes slow and a bit of a slog. And yet, they are doing the legwork for the rest of us, investigating the history of our martial systems and trying to separate fact from fiction and wheat from chaff.

I still can read “academic” more or less. Thankfully, the writers in Martial Studies are better than most and are blessed with a subject matter with more juice than the stuff I read on Virginia Woolf and Postmodernism back in the day.

It helps a lot when the field is new and you are not writing in some tiny corner of the subject. These guys, like Ben himself, Jared Miracle, Charles Russo, and so on, can write the broad strokes and big ideas. In 20 years, the the academics who follow in their footsteps will be doing articles on the Marxist Implications of Drunken Boxing Practices in 1920s Shanghai and the like.

Now with Kung Fu Grip! How Bodybuilders, Soldiers and a Hairdresser Reinvented Martial Arts for America by Jared Miracle (what a cool name!) is a new book taking a fresh look at some elements of recent martial arts history. Dr . Miracle (yes, I know, he sounds like a superhero, but he actually has a PhD. in anthropology from Texas A&M) covers a wide range of subjects in this book, but they are all really one — where do our ideas about physical power come from?

He examines the development of physical culture in the US (from Dr. Kellogg to Eugene Sandow and Superman) and shows how this intersected with the arrival on our shores of the Asian martial arts (through American servicemen, Japanese and Chinese immigrants, and especially through TV and the movies).

The area I found most fascinating in this book (and this is a thread that has run through all the books I’ve read recently on the culture of martial arts) is how our ideas and even histories have been overtly manufactured, invented, and often, completely made-up!

In my articles, I often taken the Chinese martial arts to task because of the high BS quotient in our arts. This BS quotient has led directly to such counter-reactions as Bruce Lee’s anti-“Classical Mess” arguments, Joe Rogan’s comments about kung fu , and a general outpouring of disrespect against Chinese fighting systems.

But from reading Miracle’s book (and other martial histories) its clear that much of what has been preached as gospel and factual history in martial circles was completely made up or have origins quite different from what you would expect.

Highlights of Now with Kung Fu Grip!

Bujutsu was an overall category referring to classical Japanese martial skills (formed from the characters for “war” and “skills”). Budo – self-cultivation “often have little to do with practical fighting ability.” Formation of Budo linked to 1876 ban on carrying swords in public.

Kano Jigoro (1860 – 1938) was an educator with an interest in unarmed fighting arts (jujutsu) and “modern scientific rationality.” Against his father’s wishes – jujutsu associated then with tough young men of lower social classes – he studied fighting and then formed Kodokan (“Place for the Study of the Way”). He created Judo by “having his students engage in rigorous sparring matches to test the validity of different techniques.”

Much of his modifications were really westernizing. He shifted from the old approach (I do it to you and I do it to your classmate then you try and figure it out) to a lecture leading to practice with critique approach (western). He made the study more academic. He “eliminated weapon techniques, strikes, and the more dangerous throws, hold, locks, and chokes” so the training could be engaged in without fear of significant injury (similar to the development of Chi Sau in Wing Chun!).

The book asserts that the concept of Bushido was actually developed in 1900 and disseminated through Inazo Nitobe’s book Bushido . Both the idea of Bushido and Judo were “formulated under heavy Western influence.” The Japanese reacted dramatically to the British oppression of China and the “gunboat diplomacy” of the US (we parked a fleet off their coast). The didn’t want to be subject to the same unfair trade practices (at the point of a gun) as China was relative to the UK. Politicians used training like Judo and recently invented militaristic philosophies like Bushido to justify their empire-building goals.

Kano Jigoro’s desire was to have Judo included in “physical education curriculum in teacher training colleges,” which was a system overseen by three people, two of them German. So “Judo’s most formative period saw it transformed to pass approval by an organization more German than Japanese.”

Of course, the Chinese also imagined much of its martial history!

Miracle points out that “distinguishing between the real and imagined historical narratives is particularly difficult with regards to Chinese culture” (something I have often noted from first-hand observation in my Wing Chun studies).

Chinese Highlights

A 16 th century novel The Water Margin depicts peaceful local Hans forced to fight against foreigners (Manchu) using their martial skills which were basically supernatural superpowers, such as we see in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (and many kung fu movies). Bruce Lee brought with him a Wing Chun-based realistic style of Chinese fighting which influences fight choreography to this day.

Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan was 17 th Century novel which references a Buddhist monk from India teaching fighting skills to Shaolin in 6 th century (Miracle notes this is a “historically inaccurate legend”). This book seems to be the first occurrence of distinction between “external” fighting styles like Shaolin and native Chinese “internal” skills related to Taoism. The book seemed to be making these points in an effort to favor the local (Taoist) over the “foreign” (Buddhist aka Shaolin).

Basically, like a lot of things in Chinese Kung Fu, it was Anti-Manchu propaganda.

So fundamentally, kung fu didn’t really come from Shaolin and there is no such distinction as internal vs external (outside of the mind of the novelist). You can see how various teachers hopped onto some of these various ideas and narratives for their own purposes, whether it was to support the Han vs Manchu thing or to promote their art as being magical.

This has left modern students and teachers to struggle against the propaganda and to contend with teachers who claim to have magical powers and to be descended from superhero Shaolin monks. I hope this book (and others like it) will help to start clearing the fog of superstition so we can see clearly the amazing (but not magic) system we’ve inherited from the real innovators of Chinese boxing. Sifus such as Wong Shun Leung, Gary Lam, Wan Kam Leung, Philipp Bayer, Cliff Au Yeung, David Peterson, Nino Bernardo, John Smith, Greg LeBlanc, Jerry Yeung, Philip Ng, and many others, have brought this fighting science out of the mists of mythology and placed it ever more firmly on the path to be understood, studied, analyzed, and perpetuated.