Outlive: The Science & Art of Longevity

November 08, 2023

“Although average global life expectancy more than doubled between 1800 and 2017 – from 30 to 73 years – the report says the proportion of people’s lives lived in poor or moderate health has remained unchanged at 50%.”

“If I want to live to 100, what do I have to physically be able to do to be satisfied with my life?”

Dr. Peter Attia

Yes – I want to live to be very old (maybe even 100+) if I can be physically capable of having a satisfactory life. So what do we need to do now to have the best chance for that?

Over the last three or four years, I’ve been slowly shifting the focus of how I spend my “disposable time.” After 20 years of focusing on the goal of becoming a capable fighter through the Wing Chun system and other methods, I’ve shifted gears. I turned 60 last year and this corresponded with an escalating series of injuries over the last five years, particularly to my shoulders. Nothing terrible, but a slow attrition which reduced my ability to train and sidelined me periodically. So I started thinking, are these injuries going to be chronic in my old age. Old age being something I might already be experiencing!

One of the sources I used to inform my shift in focus was listening to The Drive podcast by Dr. Peter Attia, who I first learned about from The Tim Ferris Show . According to Attia’s website :

“Peter earned his M.D. from Stanford University…He trained for five years at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in general surgery…spent two years at NIH as a surgical oncology fellow at the National Cancer Institute…(and) has since been mentored by some of the most experienced and innovative lipidologists, endocrinologists, gynecologists, sleep physiologists, and longevity scientists in the United States and Canada…(He is) a physician focusing on the applied science of longevity…(dealing) extensively with nutritional interventions, exercise physiology, sleep physiology, emotional and mental health, and pharmacology to increase lifespan (how long you live), while simultaneously improving healthspan (the quality of your life).”

So he is in a good place to give us some insight into the medical end of this question.

Starting at the Bottom

In many ways, although I’m now 60, I’m in the best shape of my life.

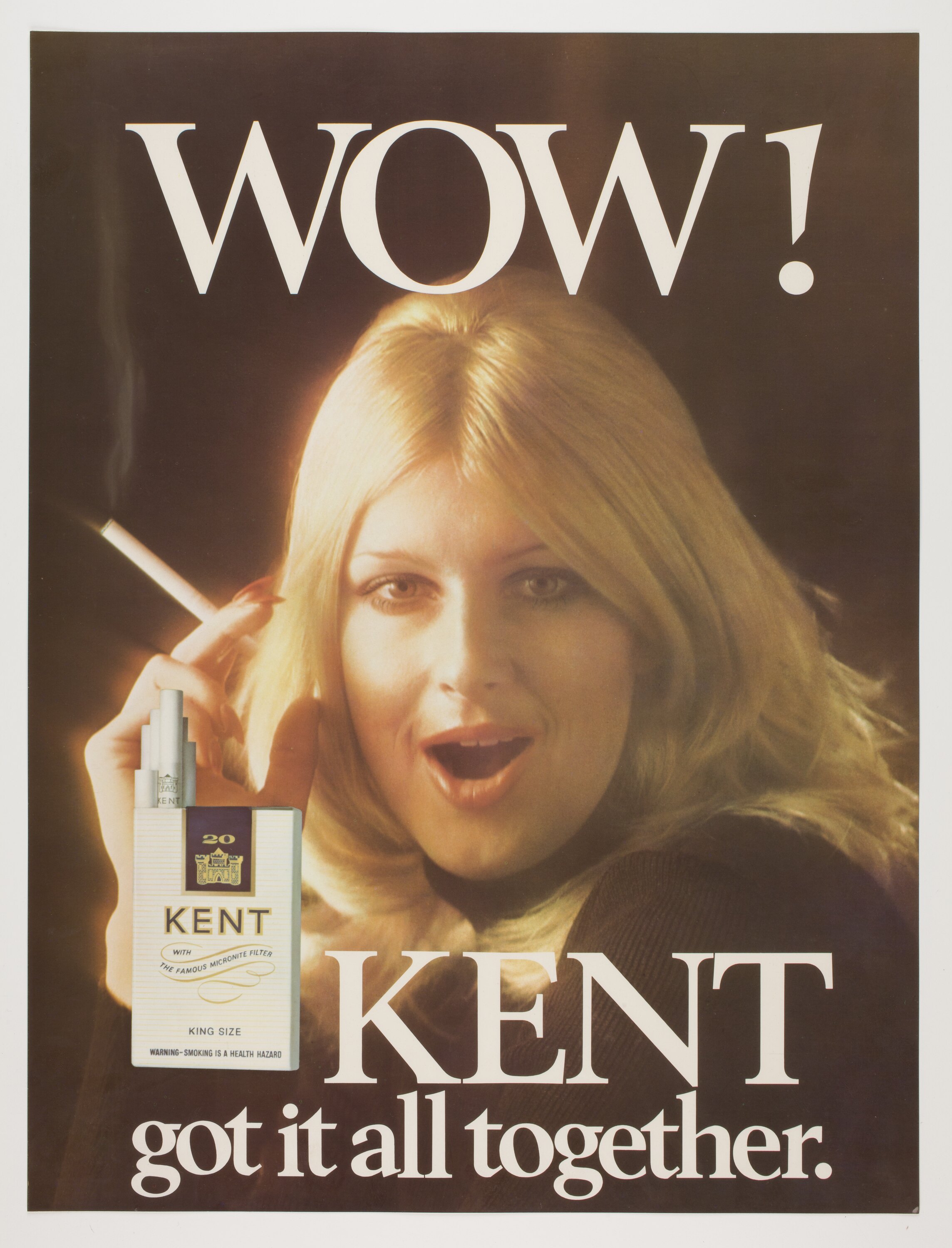

This is in part from changes I’ve made (which I will detail below), but also in part because I started off poorly. I grew up in a “typical” suburban environment in the 1960s

This is in part from changes I’ve made (which I will detail below), but also in part because I started off poorly. I grew up in a “typical” suburban environment in the 1960s

and 1970s. My parents both smoked. We ate sugar cereal for breakfast and all the vegetables we got were from a can (basically peas or corn). I never ate any seafood other than the occasional fish stick. We were Scottish-Irish, which means we didn’t use spices in our food, not even pepper. There was a lot of meat cooked to within an inch of its life. I ate a ton of sugar (candy bars, soda, sweetened iced tea). I started smoking at 16. Throughout my military career in the early 80s I smoked a pack a day, and ate candy bars for breakfast from the machines in the break room, and washed it down with Mountain Dew. Breakfast of champions. Or the malnourished. One of those.

and 1970s. My parents both smoked. We ate sugar cereal for breakfast and all the vegetables we got were from a can (basically peas or corn). I never ate any seafood other than the occasional fish stick. We were Scottish-Irish, which means we didn’t use spices in our food, not even pepper. There was a lot of meat cooked to within an inch of its life. I ate a ton of sugar (candy bars, soda, sweetened iced tea). I started smoking at 16. Throughout my military career in the early 80s I smoked a pack a day, and ate candy bars for breakfast from the machines in the break room, and washed it down with Mountain Dew. Breakfast of champions. Or the malnourished. One of those.

Between 1979 and 1989, I didn’t do much in the way of exercise, aside from playing around with the Karate I’d learned in High School, the way you’d take your motorcycle out for a spin on weekends. Being in my 20s, my body allowed it. There were no consequences yet, relative to what I was trying to do. I did have a hard time each year doing the physical fitness tests the military imposed.

In ’89, after a long buildup of dissatisfaction, I finally developed some willpower and made big changes. I quit smoking (using a method I invented myself I call the William James Method ), I tightened up my diet, and put in 18 solid months of weight training three days a week. I was working in a college library after getting my BA, so I was surrounded with information. I read a book called Sugar Blues in college and cut out sugar for about three years around that same time. I started trying some running and swimming. I gained 20 pounds of muscle and improved my cardiovascular capacity substantially (as well as my dating options).

I don’t know how useful college degrees are, really, but in my case I learned how to work hard and how to do research.

I began applying these new skills to all my goals. I started a concerted effort to learn about nutrition, to learn about the best methods to become stronger, faster, healthier. And eventually, I started becoming aware of the concept of longevity . No one in my family were what you might call “healthy.” Most of my role models were smokers, drinkers, non-exercisers, and eaters of junk. I guess my awakening to the concept of improving health coincided with the shift in society. In the late 70s and early 80s, we started hearing about health food and yoga and aerobics. Body building became a mainstream thing with the arrival of Arnold Schwarzenegger on the scene (although it got a shot in the arm from none other than Bruce Lee).

I had a another big shift in my attitude toward health when I read a book back in the late 1990’s (when I was in my late 30s) which focused on aging intelligently, called something like Health After 40 . The book suggested certain kinds of vitamin supplementation, certain kinds of exercise (weight training, cardio), drinking lots of water, and certain approaches to diet, all directed toward improving something the writer called “health span.” These were ideas that would later percolate throughout the culture via the internet.

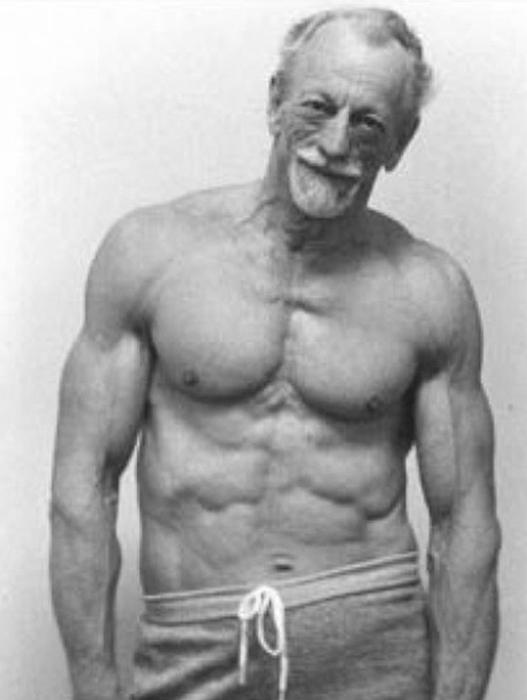

That book left me with a strong desire to not lose the gains I got in that period after college, but to keep putting in foundational work so I could have a healthier, stronger older age. I started having this vision of myself in my 80s being strong and active. Around the same time, I was using a gym that had a picture of this guy (to the left) in the hallway. I started to think about actually having another 40 or 50 years of health ahead of me. I wanted to look like him when I was 80.

Throughout the first decade of the 2000s, I tweaked and improved my diet and exercise programs. This vague idea was given a big shot in the arm when I started hearing about Dr. Attia (and others in this longevity space).

Centenarian Olympics

Dr. Attia began framing his longevity ideas around a concept he calls the Centenarian Olympics around 2014, which became the central concept of his book Outlive . He describes the concept and then explains how Medicine 3.0 (preventative) will give you the best opportunities to compete in your tenth century.

Your endurance, your strength, your flexibility, your balance and most every other physical capacity you have now will decline continuously, and more and more rapidly, like a series of hills and cliffs you are sliding and falling down, as your pass 30, 40, 50, 60, and so on toward the human maximum, which is currently somewhere around 100. Most people in their 60s (never mind 70s, 80s, 90s) are frail. Their bones are smaller. They have lost major percentages of the muscle they had at their peak (this steady muscle loss is called “sarcopenia”).

Average life expectancy is in the high 70s to low 80s. Some people (not Snake vs Crane readers, but some people!) say things like, “why bother, you put in all that work, but you still get old and die.”

Yes, we all will still get old and die, but check out this chart on the left. This corresponds to my observations. Science is getting better and better at keeping us alive. They just don’t address quality of life very much. I have a number of relatives who smoked and ate poorly and didn’t exercise much and they lived into their 80s (and in one case, 90s). But their quality of life sucked! They could barely move. They had a laundry list of ailments that were extremely unpleasant to suffer for weeks, never mind decades.

If this chart to the left is accurate (I’m sure its just a ballpark), then about 30% of us are going to make it to 90! But the decline begins at 30! So if we don’t take action now, our lives are going to be a sorry state of affairs for that last stretch of 20-30 years.

The way Dr. Attia went about it was to reverse-engineer the question. How long can we hope to live?

Well, the most you can expect is in the ballpark of 120 years ( Jeanne Calment lived to 122). Most people don’t live much past 79, in the US. But he’s thinking, let’s say I make it to 100. That seems like a decent goal these days. Shoot for the moon, maybe you’ll hit a star! OK – if we live to 100, and we hope to have quality of life, what should our physical capabilities be? Let’s make a list of these “desired capabilities at 100,” and then reverse engineer back to now, and start planning. How I should train now to hit that future mark?

He details some of his benchmarks in the article “ How to Train for the “Centenarian Olympics. ” Some of his physical aspirations for his centennial are he wants to:

- Be able to play with his potential future grandkids and even great grandkids – so be able to drop into a squat position and pick up a child that weighs 30 pounds.

- Get up off the floor with a single point of support (i.e. using just one arm).

- Lift something that weighs 30 pounds over his head (say a suitcase into an overhead bin).

- Get out of a pool without a ladder.

And so on. It’s a useful thought experiment! And based on this line of thinking, he suggests we think about these four components of physical capacity.

- Stability

- Strength

- Aerobic Capacity ( Zone 1 , like walking normally and Zone 2 – steady medium heart rate over a longer time period, such as running or biking for an hour)

- Anaerobic output (Zone 5, such as Sprinting – high heart rate for a short burst)

“One purpose of the Centenarian Decathalon…is to help us redefine what is possible in our later years and wipe away the default assumption that most people will be weak and incapable at that point in their lives.”

Peter Attia, Outlive

So how do we work on these four areas? He has his recommendations in the book and article, and I have my own activities based on thinking along the lines of “this is what I have the time for and am willing to do”

Stability

This is a big one. Many older people fall over and break something and this is often initiates a fatal decline. Even a brief stint in the hospital or on the couch can result in a catastrophic loss of muscle mass and strength. We need to head this off by staying strong and training to maintain our balance.

“As a result of loss of muscle mass, up to 40 % of muscle strength can be lost within the first week of immobilization.”

article in the National Library of Medicine

Dr. Attia recommends a form of training called Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization . Well, I live near Oakland, California so I have access to a lot of great resources (martial arts classes, yoga, Pilates, etc). But DNS is not available here. Plus it sounds expensive!

This is my suggestion for this area. For years (ever since I was in High School doing Karate) I have trained balance (back then to improve my kicking). I put on my shoes standing up a lot of the time. I still train kicking, only I do it slowly and not ballistically. I am studying Tai Chi, which involves moving from stance to posture to kick to stance slowly, keeping precise control of balance.

Strength

Dr. Attia promotes doing the multi-joint exercises like Deadlifts and Squats, and these are really the most efficient way to realize big gains (see Starting Strength etcetera). But I also find that to get decent gains using those heavy movements, you have to eat a lot, and this results in a fat gains alongside the muscle gains and its just not easy to make that switch, from lifting heavy and eating heaving, to cutting the fat through dieting.

“The sad fact is that our muscle mass begins to decline as early as our thirties. An eighty-year-old man will have about 40 percent less muscle tissue…than he did at twenty-five…we lose muscle strength about two to three times more quickly than we lose muscle mass.”

Dr. Peter Attia

It takes much less time to lose size and strength than to gain it. In one study, participants lost 3.3 pounds of lean muscle mass in just 10 days of bed rest. To put that in context, that time I lifted for 18 months and put on 20 pounds of muscle (back in my 20s), I then got a stomach virus and lost most of that muscle in a month of inactivity and reduced eating. So its tricky! And its tough to put muscle on past the beginning stages.

“it’s rare to see a natural bodybuilder or fitness enthusiast close to their genetic muscular potential gain more than 2-3 pounds of lean muscle in a year.”

Obi Obadike, M.S., Bodybuilding.com

I’ve found that there a a few keys, in practice, to building and maintaining muscle for an ordinary person.

One, this isn’t a race. I gained that 20 pounds of muscle at age 27-28. Since then, I’ve been training off and on. Now I’m 60 and I’m 6 foot and weigh 190, mostly lean muscle (a little soft around the middle!). I have been a bit more on and off than I would recommend and I’ve learned over time to cycle things to keep my interest up. I took a kettlebell class and now I do swings and the Turkish Get Up. I took a basic weightlifting class in which we were closely monitored doing the big 4 (Squat, Bench, Deadlift, Overhead Press). I’ve adopted things like In and Outs, Bear Crawls, Farmer Carries, Bar Hanging, and so on, so I have a program I’m working, but I can also just go in and do a decent off-the-cuff workout. I find it keeps me from dropping out (as I’ve done many times in the past).

One recommendation I have is take some training classes. Yes they cost a lot of money! But this can work for you. It kicks in the “sunk cost” mindset. I spent such and such an amount of money on this training – now I need to get the benefit by doing it and getting the benefit. Plus if you learn it right, you will avoid injuries.

When you think that I’ve been working out now for over 30 years, you realize you have time. Take the long view!

To Be Continued in Part 2